Coatlicue-Nefertiti by Perla Arroyo, one of six representations of the Mexican Skull®.

7 de March de 2022

Death is democratic, since, at the end of the day, whether black, brown, rich or poor, all people end up being skulls.

José Guadalupe Posada.

Text by: Luis Ignacio Sáinz

Our creator proceeds from reflection, without turning her back on plastic and spatial intuition, and this research will be the origin of the Calavera Mexicana® project, aimed at making this symbol of popular culture visible by contributing her own elements and vision. Posada’s garbanceras, fatigued and recovered by Diego Rivera so that they would not succumb to the quality of mummies or be limited to their condition of vectors of criticism, are re-signified from their awakening: that of the mother of the gods, Coatlicue. The visitations allowed and suffered by the most beloved of Mexican bones show various attributes of the progenitor of Coyolxauhqui (“the one adorned with bells”), dismembered by her own half-brother born from a feather fallen from the sky, Huitzilopochtli (“hummingbird of the left”), who impregnated his own midwife.

Perla Arroyo, without adjectives, renounces grandiloquence and avoids the banality of this hackneyed, vulgarized form that has turned the skull into a puerile symbol, devoid of full content. It is about empowering an emblem or icon (εικόνισμ, image): sum of figure and concept, which performs as a fertile sign (union of signifier and signified). Calavera is a feminine noun from the Latin calvarĭa, meaning skull. In addition calvarium (place of skulls) will designate a deposit, ossuary, as a place of penalties. Miscellaneous bony components of the head, united but flayed, which correspond to the term calavera (testa or helmet).

The person responsible for these compositional twists and turns is wary of appearances, she insists on searching for the underlying structures. It belittles or disdains epithelial beauty, that shell which, by containing and covering us, also deceives and bewilders, since it offers a frivolous vision of our animate being. Against the current, for the sake of encountering the primordial solidity, the ability to designate, invent and analyze the environment and its elements, identifies the hard tissue that contains our most precious jewel, the brain, and crowns it with a headdress in whose core appears in its defiant splendor the head formed by a pair of scaly serpents, with huge and threatening fangs, their jaws meeting as if they were flirting, a sort of seal flanked by a flower (xōchitl) multiplied in a border.

Reference to the duality life-death, sacred-profane, in the transit from the earthly to the cosmic and its return to fulfill the journey of the weltanschauung (which I understand more as “intuition of the world” than as “cosmovision”) Mesoamerican: the continuity without rupture of poles that are never opposites, but phases of the process of being and its manifestations that involves different layers of meaning: intellectual, emotional and moral (Wilhelm Dilthey: Einleitung in die Geisteswissenschaften, 1914).

Coatlicue (“the one with the skirt of snakes”), also named Tonantzin (“our revered mother”), in her best known lithic representation was found on August 13, 1790 during the leveling and paving works of the Plaza Mayor at the initiative of Juan Vicente de Güemes Pacheco de Padilla y Horcasitas (Havana, April 5, 1738 – Madrid, May 2, 1799), II Count of Revilla Gigedo, at the time 52nd viceroy of New Spain (1789-1794). The monolith of the decapitated woman was hidden to the southeast of the central esplanade, next to the Palacio de los Virreyes, and was studied by Antonio León y Gama (1735-1802), without being given that name at the time, proposing a fusion of the divine couple formed by Teoyaomiqui and Teoyaotlatohua Huitzilopochtli, whose base shows Mictlantecuhtli. The author comments on the flint used: “Its material is of the species of sandstone described in his Mineralogy by Mr. Valmont de Bomare, hard, compact, and difficult to extract fire from it with steel; similar to that used in mills”.

Moved to the lower ambulatory of the university courtyard, she regained her devotional prominence, being the object of various offerings, endowed with candles and syringes, in spontaneous popular veneration, which caused anger and dread in the friars and the authorities, so they chose to silence her, burying her in the cloister itself. They threw earth on it to silence it; useless burial. Shameful burial of Huitzilopochtli’s mother, betrayed by her daughter Coyolxauhqui and her offspring the Four Hundred Surians. Benito María Moxó y Francolí (Cervera, Catalonia, 1763-Salta, Argentina,1816), ordained Benedictine monk, who in 1804 was consecrated auxiliary bishop of Michoacán under the orders of Fray Francisco Antonio de

“During the time that the re-leveling work lasted, the time was used to install large stone covers and pipes that would carry water to four new and slender fountains, one at each corner of the square. In addition, sidewalks and wheel guards were built, and the area was paved. Finally, the Acequia Real was embanked, eight piers were built with double stairs and the small boxes of San José, located at the southern end of the plaza, in front of the Portal de las Flores, were demolished”: see López Luján, Leonardo: “El ídolo sin pies ni cabeza: la Coatlicue a fines del siglo XVIII”, in Estudios de cultura náhuatl, Mexico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, vol. 42, 2011, p. 203-232. Bernardo Bonavía, superintendent and corregidor of Mexico City, José Damián Ortiz de Castro, master builder of the city and in charge of the work, José Antonio Cosío, principal superintendent.

Antonio León y Gama: Historical and chronological description of the two stones that were found there in 1790 on the occasion of the new paving that is being built in the Main Square of Mexico City. The system of the Calendars of the Indians is explained, the method they had of dividing time, and the correction they made of it to equalize the civil year they used with the tropical solar year. News very necessary for the perfect understanding of the second stone: to which are added other curious and instructive on the Mythology of the Mexicans, on their astronomy, and on the rites and ceremonies that were customary in the time of their gentility.Mexico, Imprenta de Don Felipe de Zúñiga y Ontiveros, 1792. [Vl]-116 p. ills., p. 1-8. There is a modern edition by INAH.

San Miguel Iglesia Cajiga (Revilla, Cantabria, 1724-Valladolid, Michoacán, 1804), who ordered the construction of the Morelia aqueduct, in the Cathedral of Mexico by Archbishop Francisco Javier de Lizama y Beaumont (1749-1813) of whom Manuel Tolsá made the burial mound, is credited with the decision to bury the 24-ton goddess.

Such a parade of life prowls through the bald head, plundered of its layers and integuments that usually protect it and endow it with a unique personality. Synonyms of harmony and beauty that equally resonate with the goodness attributed by the indigenous cosmogony to this metaphor of life beyond life (tzontecomatl, skull; cuaitl, head), its course in the pilgrimage in the underworld (Mictlán). Arroyo’s skull keeps a certain hieratism, a sacred and immobile something that summons us to unravel its enigmas and secrets. She screams towards the four cardinal points, exhausted, without uttering a sound. He longs to share his pains with us: his hair cut off at the cap, perhaps hidden in the hollow of the imperfect cylinder that serves as a scarcella and covers the summit of his being.

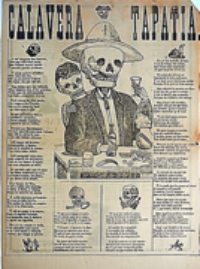

However, its representation keeps a certain distance from the “skeletal” popularity that we owe to Manuel Manilla(Calavera tapatía; flyleaf from the workshop of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo; 1890), which would exalt José Guadalupe Posada to delirium(Remate de calaveras alegres; flyleaf from the workshop of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo; 1913).

Although her universal fame is due to Diego Rivera, who would definitively baptize her as La Catrina and make her the center of the A dream of a Sunday afternoon in the central Alameda (1947), a mural in which the artist from Guanajuato collaborated with Rina Lazo, where “la huesuda” appears for the first time in full body, dressed, covered with a feather stole and flanked by the artist as a child, pampered by Frida Kahlo, and the engraver from Aquicalid. Letter of naturalization for the good death that in this presentation in society is accompanied by more than one hundred characters of national history in a hodgepodge eccentric to the extreme, among them and located towards the ends, Benito Juarez and Porfirio Diaz, while posing serious Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, the emperor Maximilian, the apostle of democracy Francisco I. Madero and Hernan Cortes, Manuel Gutierrez Najera or Jose Marti.

So Perla Arroyo’s three-dimensional representation draws from other transatlantic sources: the subgenre of the Vanĭtas (from the Latin, vanus: empty), belonging to the geography of still life, as a sobering memory of the ephemerality of power, wealth and beauty, very visible in the art of the Baroque, emerging in Flanders and the northern provinces, now Holland, to later settle in its own right throughout Europe, with a certain predilection for ancient Sepharad (toponym of Spain; in Hebrew, סְפָרַד), named in the Old TestamentBook of Obadiah. Designation originally rooted in Ecclesiastes (Eccl. 1, 2): Vanitas vanitatum et omnia vanitas, “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity”. A senequist sentence that underlines the insignificance and futility of existence. Further on in the same biblical text (9: 10) it is stated: “…for in the grave, where thou goest, there is neither work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom”.

No fuss, Coatlicue-Nefertiti It manifests an air of seriousness and transcendence, it is not intended to be playful or circumstantial, but rather an announcement of an intangible, philosophical, spiritual vitalism in the broad sense (alluding to the immaterial dimension, endowed with intelligence and reason, sensitive, meditative experience, far from the temptations of the world, the flesh and the devil). Lazarillo in a journey into the depths, beyond the obvious, anchoring in the marrow of our most resting and nourishing convictions. Root claim that disrupts the stereotype.

Allegory of Vanity (1632-1636) – Knight’s Dream (1650).

Among the effigies of Coatlicue preserved in the National Museum of Anthropology, two stone portents stand out, each of them obeying its own compositional and constructive paradigm: one more allegorical and geometric, a tremendous stone monolith that supplants the divine head or emphasizes that the divine head is the collision of a pair of snakes; another, more humanized and figurative, a spectacular carving where the feet were mutated into aquiline claws and the head looks flayed, its skin isisada. The first emerged from the subsoil in the vicinity of what we call the “Zócalo”; the second was found in Coxcatlán (in Nahuatl, “place of those who wear necklaces and chokers of beads”, a string of stones), in the Sierra Negra of Puebla, bordering Oaxaca, where corn was domesticated.

In 1843, at the initiative of Antonio López de Santa Anna, the design and construction of a monument to commemorate the independence of Mexico, the winner was Lorenzo de la Hidalga (1810-1872), with the project of a column in the center of the square. The prevailing instability watered down the proposal, and only the location was placed: the plinth or baseboard, precisely. The nothingness ended up imposing itself and the part supplanted the whole, and since then the viceregal square called the Constitution (1813) in honor of the fundamental Spanish law sworn in Cadiz a year before was baptized as such.

A sculpted rock of solitary beauty that sows awe by flaunting its attributes that link it to fertility, death and certain supernatural beings of the night sky. Could she be the heiress and successor of Yolotlicue, the one with the skirt of hearts, her twin, found in 1933 by Alfonso Caso in Seminario and Guatemala? Would both be the idols that presided over the altar of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan according to Andrés de Tapia?

Military man and chronicler from Extremadura (c.1497-1561), major mayor of New Spain and major steward of the Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca, among other positions. Author of the Relación de algunas cosas..., which gives an account from the departure of Hernán Cortés from Cuba to the defeat of Pánfilo de Narváez on May 24, 1520 in Cempoala, Veracruz, sent to subdue the rebel conquistador.

Sculpture representing Coatlicue, being at the same time a tremendous and fascinating figure, numinous in the sense of the hierophanies that Rudolf Otto identifies with the holy (Das Heilige, 1917). Powerful divinity that confirms that death generates life, nourishing it from its (apparent) decomposition. He was located in CoxcatIán, Puebla. It retains the turquoise and shell tesserae that decorate its face and eye sockets.

The Calavera Mexicana® series forges some very unsuspected unions, such as that of Coatlicue with Nefertiti, a goddess of gods and a divinized pharaoh’s consort, milking semantic possibilities wholesale. This means taking full advantage of two manifestations of thinking: divergent thinking, the ability to provide (multiple) solutions and higher-order responses to the same stimulus; and convergent thinking, the ability to deduce a single correct solution using systematic rules. The Siamese condition of the resulting sculpture demonstrates a conception in action of creativity capable of articulating flexibility, originality and linguistic fluidity oriented to its objective materialization. If we are unable to designate what we create (postulate a phenomenal constellation), even at the level of a constructible fantasy, we will be unable to fabricate it in reality (structure a synthesis of multiple determinations).

Let us now review in its generalities, the woman ruler of the Egyptian empire, as a historically existing object and as an iconically representable subject. Both dimensions come together in a more than 3,300-year-old bust of Queen Neferneferuaton Nefertiti (c. 1370 B.C.- c. 1331 B.C.), whose name means “beauty has arrived”. Wife of the pharaoh Amenophis IV (later called Akhenaten). Queen in 1382 B.C. who, due to her enormous earthly and religious power, achieved such an influence that the figure of the woman, the family and the couple were worshipped.

In all reliefs and paintings she appears as an archetype of feminine strength, virtue and delicacy. As a work of art Nefertiti passed through different locations, until she returned to the restored New Museumamong 35,000 other pieces, including the statue of her husband, the tenth pharaoh of the XVIIIth dynasty (1352 to 1337 B.C.), as well as the portrait of Queen Tiy, and 60,000 papyri from the Amarna collection of the modern Egyptian Museum in Berlin.

After its rediscovery, it was acquired by the German-Jewish businessman and collector Henry James Simon (1851-1932), one of the founders of the Deutsche Orient Gesellschaft in collaboration with Wilhelm von Bode, who sponsored the archaeological excavations that led to the discovery of this exceptional portrait. Limestone bust with painted stucco (50 cm and 20 kg). It is believed that Thutmose made it in 1345 BC, because on December 6, 1912 Ludwig Borchardt (1863-1938) found it in his workshop in Amarna, on the east bank of the Nile, Khedivate of Egypt ruled by the dynasty of Mehmet Ali, as a tributary state formation of the Ottoman Empire, after the expulsion of the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Built by Friedrich August Stüler (1800-1865), disciple of Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841; notable works: Glienicke Palace, Nazareth Church and Charlottenhof Palace), following the guidelines of late classicism from 1841 to 1859 and rebuilt between 2003 and 2009 by architect David Chipperfield.

The portrait of Nefertiti, wife of Amenhotep IV (also known as Akhnaton or Amenophis IV), the sovereign who elevated her to the altars, signed by the artist, a truly unusual case, sculpted in limestone, stylized to the extreme with an infinite neck, with a headdress covering the head in black, decorated in gold and colored stripes, showing in high relief an Egyptian “cross”, hieroglyphic named Ankh (“life”; emblem perhaps representing the strap of a sandal, a mirror or the union of the male and female genitalia).

The aforementioned Ludwig Borchardt commissioned a chemical analysis of the pigments used. The results of the examination were published in the 1923 book Portrait of Queen Nofrete:

- Blue: frit (vitreous material of inorganic origin) in powder form, colored with copper oxide.

- Light red: skin color, fine powdered lime powder colored with red chalk (iron oxide).

- Yellow: oropiment (arsenic sulfide).

- Green: frit powder, colored with copper and iron oxide.

- Black: charcoal with wax as a binding medium.

- White: chalk.

When the portrait was found there was no piece of quartz to simulate the iris of the left eyeball, as in the other eye, and none was found despite an intensive search and a significant reward of £1000 for information on its whereabouts. The missing eye led to speculation that Nefertiti may have suffered an ophthalmic infection and, in fact, lost her left eye, although the presence of an iris on other statues of her contradicted this possibility. Borchardt assumed that the prosthesis fell off when the creator’s workshop fell prey to neglect and ended in ruins.

Dietrich Wildung proposed that this was a model for the serial production of official portraits, used by the preceptor to teach his pupils how to produce the internal structure of the eye and, therefore, the left iris was not added. Gardner’s art through the ages: the Western perspective by Helen Gardner, Fred S Kleiner and Christin J. Mamiya offer a similar version concurring that the bust was kept deliberately unfinished.

There is no doubt that the great civilizations do not reveal themselves completely, they keep certain arcana in the dark and impose on their heirs the audacity to formulate hypotheses, sometimes far-fetched, sometimes simple occurrences. The abysmal age differences, perhaps existence is a better term, between Nefertiti and Coatlicue, in this case also her twin Yolotlicue, disappear before our ignorance: we do not know more than we think we do. Thus, delving into the secrets of both representations, dazzling iconographies of bulk, becomes permissible, but it could be left over. It is not superfluous to evoke the Stagirite: “It is the form that is expressed, and each thing is designated by its form; one should never designate an object by its matter”. The plasticity of the works dispenses with their own contextualization; while information of intent and purpose potentially enriches their appreciation, the strictly aesthetic character does not suffer in its absence.

Now, the dilemma resides in the fact that the form is imbued with matter, being able to be sensible (the physical factors: the stone and its pigments and grafts) and/or intelligible (the comprehensible factors: the attributes of the deity). Remember that when the Coatlicue makes her “appearance” (a sort of revelation to non-believing mortals, the peninsular and novo-Hispanic masons and bricklayers) she sows a hermeneutical discord between Alzate and León y Gama, regarding her very identity, which will be resolved in time. This means that its mere material recognition and the empathy it generates as a form transcend its proper name.

Perla Arroyo affirms her Mexicanness in the recognition of contributions from other latitudes. Their desire to know is complemented and enriched by the views of those others who are interlocutors and not adversaries. The sustained character, the integral nature, of Nahuatl thought, constitutes the backbone of her visual reflections, which make her a worthy heir to the ancient tlamatinimethose wise men from afar who “knew things”, and tlacuiloquethose who “wrote by painting”, or in this case sculpting and modeling in 3D. His is a contemporary look, a kind of syncretism that emphasizes, I insist, dynamic continuity, because change is an immanent value to this philosophy, where accidents and chance are valued and incorporated into the flow of the represented reality, as form, as reflection. This is the meaningful universe of the Coatlicue-Nefertiti, part of the Mexican Skull® series.

BOLETÍN

* Llenado obligatorio para continuar

Al suscribir aceptas los términos, políticas y condiciones de este sitio web.

Podrás cancelar tu suscripción a través del correo que recibas de nuestra parte en el momento que desees.